By KRISTYNA BROZOVA

Women and men experience the world differently and are impacted in different ways. Even though both suffer during economic slumps, these setbacks disproportionately affect women, who tend to be in a worse position to begin with. International crises, such as the financial crisis on 2008 and the COVID-19, further magnify gender inequalities, making it harder for women to achieve an equal position in the society. Three decades after Cynthia Enloe asked ‘Where are the women?’, the question of women’s position in the world remains a neglected discussion across all levels of society.

Growing Inequality

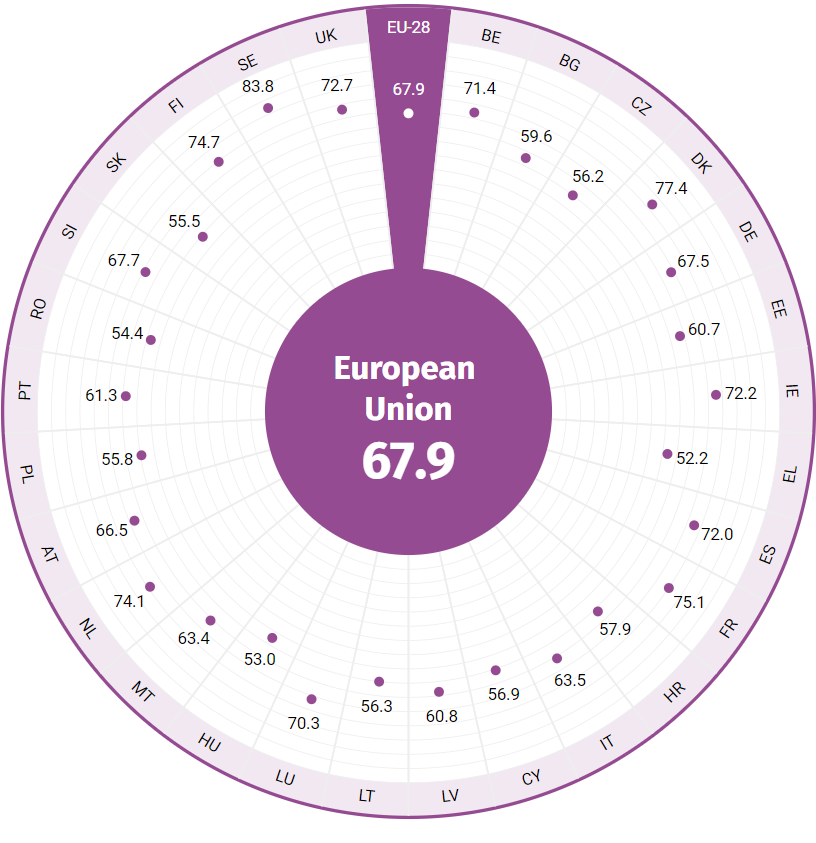

When it comes to the international economy men and women have always experienced crises in different ways, mainly due to the differentiated perception of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ labour. Historically, women have been in a disadvantaged position, where social norms and gender segregation have shaped access to the economy. Over the years there has been some progress in the matter of gender equality, however, the Global Gender Gap Report for 2020 shows that given the current pace of progress, gender equality would be achieved no sooner than in 99.5 years. The data from Europe indicates the European Union would need almost 68 years to close the gender gap as inequalities remain in all measured indicators. Moreover, there has been no progress in Europe since 2017, which reflects a wider stagnation at the global level.

Gender Equality Index (The European Institute for Gender Equality, 2021)

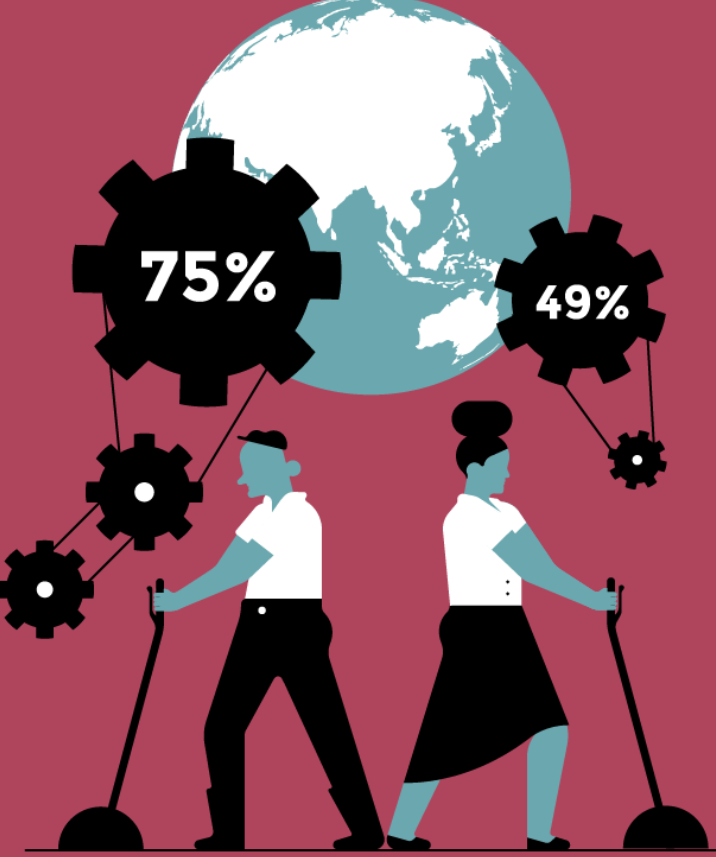

Despite the fact that women make up about a half of the world’s population, their workforce participation remains significantly lower than that of men, around 49% compared to 75% according to International Labour Organisation (ILO). Furthermore, women’s engagement has been decreasing in the past few years – from 50.99% in 1999 to 46.91 in 2020. They are absent from decision-making powers, senior positions or managerial posts – especially in banking and finance. On the other hand, they are overrepresented in the informal and unorganised economy as a part-time, low-skilled staff. They also bear unequally the burden of unpaid labour, which is globally worth 10.9 trillion dollars each year. Clearly, women are worse off even outside an economic crisis.

The global labour force participation rate (ILO, 2018)

The gap in Labour participation

The labour market is one of a few opportunities for women to better their position in society. Some may argue that men face greater job losses than women during the crisis, and this can help to narrow the gender gap, as was the case in 2009. However, the data differs when we do not limit ourselves to the Developed countries and rather look at different sectors of the economy across all geographic regions. When men and women are represented equally, it is women who will lose a job.

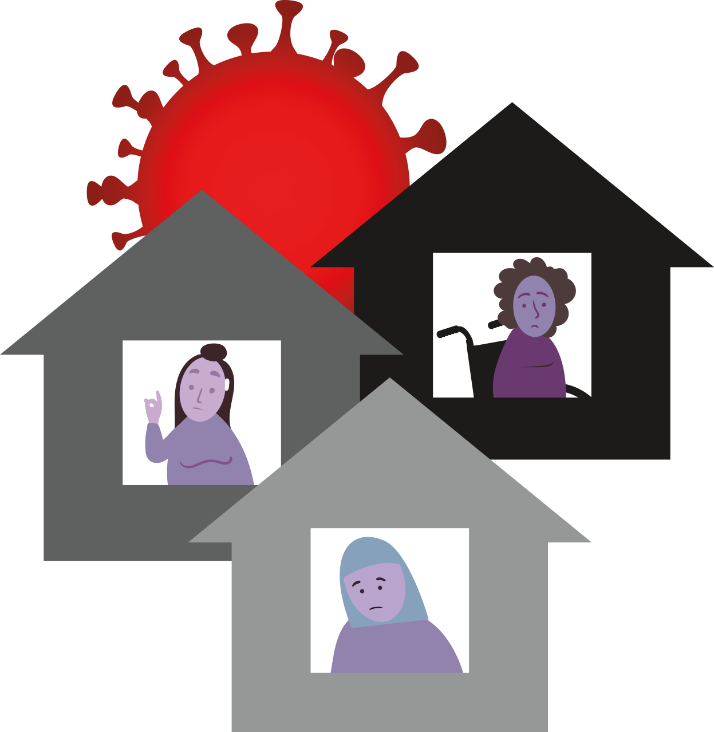

One reason why female labour force participation during a crisis is more vulnerable is the fact that men are perceived as having more right to employment when work is scarce. Women’s unpaid labour also increases significantly, making it impossible for them to continue working. Currently, with many schools and day-care centres closing, neither grandparents nor friend being able to help, the pandemic is having a significantly worse impact on women, particularly single mothers.

Gender bias and inequality within households also means that, even when it is a man who lost a job, it is the women who compensate for the lost income in protecting the lives of their family. As food becomes scarce, women go hungry, giving their food to the family, and increase their informal labour (often as sex workers). Cases of rape, domestic and sexual violence tend to grow significantly during crises, while access to help or abortion is drastically limited. Girls are forced to replace a mother and take care of younger siblings and household, which is one of the reasons why they are pulled out of schools more often than boys. Consequently, 2 thirds of the global illiterate population are women.

(Women Enabled International, 2020)

Limited access to Resources

Even though women’s rights are virtually protected by international law, women are still less likely to have access to finance, assets, property and land. They are perceived as riskier borrowers and the shortage of credit during crises makes it even harder for women to get loans, which further undermines their empowerment. They also face limitation in what they can achieve as their opportunities to get adequate training is limited. This is due to the extra hours spent on by domestic work, obstacles in accessing funds to buy technical equipment, and an existing digital divide between the genders. This is a significant limitation especially during the current crisis as the digital division makes it harder for women to adapt to remote working. It also leaves women more vulnerable in accessing digitalisation as positions in female-dominated industries are more likely to be replaced by automatization.

(Kafkadesk, 2019)

Wrong policies

Women are not affected only by the economic crisis itself, but also by the measures adopted in response. For example, governments tend to lower the expenditure on health and social care, which magnifies the already mentioned burden of childcare and limits economic support on which women rely. Also, the cost of essential items tends to grow and wages drop. This again takes a heavier toll on women, who need to buy food and medicine for their family. Moreover, many measures, such as the bailout of banks, in which women are generally marginalised, bring greater profit to men. These gender insensitive policies should be re-evaluated and replaced by more gender-aware, structural responses focused on job creation, income security and opportunities creation, such as loans for microenterprises building or training programs.

Social change?

In contrast, crises can cause a form of social revolution, which enables women to change their position in the global economic structure. The current crisis caused by the COVID pandemic may change the existing bias as it forces more man to share domestic labour as women in key professions have to work long hours. Nevertheless, it is questionable, to what extend this outweighs the difficulties women face in the long run because progress achieved during emergencies tends to be short-lived. For example, during the First and the Second World War, many women joined the labour force but were fired as soon as the male workforce became available again. Thus, any change requires a comprehensive structural revolution rather than an ad-hoc reaction to the urgent need, which uses women only to fill a temporary shortage of talent and does not address the root causes of the inequality.

These crises are not gender-neutral and their implications are gendered. For women, economic slumps represent just another hardship they have to fight on top of every-day battles. Crises magnify existing inequalities and bring new burdens for women, setting back any progress made in the matter of gender equality, and further undermining female empowerment and emancipation. This is deepened by gender-insensitive policies adopted in response to the emergency. Although crises should be viewed as an opportunity to reverse gendered bias, such changes of social norms are usually short-lived as the society is more focused on getting back to business than on developing more progressive policies. Nevertheless, it is obvious that gender equality would be beneficial for all and should be one of the main focuses of post-Covid recovery.